This poem is a 曲 “qu” or song of the 元 Yuan Dynasty which is made up of long and short lines. Tian jing sa 天净沙 is a tune, the people in Yuan, they recited this qu 曲 poem to the tune of it.

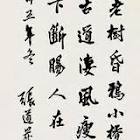

馬致遠: 天淨沙: 秋思

Ma Zhiyuan (1260-1364): Tian Jing Sha (Sky cleansed sand ): Autumn Thoughts

枯藤老樹昏鴉

Ku1 teng2 lao3 shu4 hun1 ya1

小橋流水人家

Xia3 qiao2 liu2 shui3 ren2 jia1

古道西風瘦馬

gu3 dao4 xi1 feng1 shou3 ma3

夕陽西下

Xi4 yang2 xi1 xia4

斷腸人在天涯

duan4 chang2 ren2 zai4 tian1 ya2

Withered wisteria, old trees, evening crows;

A small bridge, a running stream, a man’s house.

On an old road, in the western wind, a scrawny horse.

The evening sun is setting in the western sky.

A heart-torn man wanders at the edge of the sky.

Translated by Shu

Analysis of the Tian Jing Sha, Qiu si

There are only 28 words in the poem;language is very condensed, vividly convey the wandering mind of the heart torn roamer.

The picture consists of two parts:

A few carefully selected from the group to represent the composition of a scene of autumn sunset picture;

Second, describe the pain and endless heartaches of the wanderer’s silhouette in cold autumn horizon.

An interesting article — Poetic Angst over Time and Tense

Over at the Poetry Foundation’s blog, poet D. A. Powell comments about time in Mandarin:

DA Powell: Every sentence written in English contains some anxiety about time. I’d love to write a poem that was Time-Free. Is that possible?

ME [Rachel Zucker]: Why? Is this particular to English?

DA: I don’t think English is necessarily the only language in which time is embedded in the verbs. But I know that in Mandarin it’s easy to make a sentence that doesn’t tell you at what time things happened. And I wish that were possible in English. A sentence in English begins and ends; it has direction; it carries you, relentlessly, toward a period, a place of death. It’s why I avoided sentences for so long in my poems–because I didn’t want to feel like I was living out a sentence.

Almost boastingly, Chinese language teachers used to tell us hapless learners of Mandarin that “Chinese has no tense.” Similarly, our professors of Chinese culture used to proudly inform us that “China has no religion, only philosophy.” Thankfully, nowadays no teacher worth their salt would make such outlandish claims.

If a Chinese speaker wants to be clear about when something happened, happens, or will happen, there are plenty of resources in the language for doing so. If, on the other hand, he wishes to be vague about time and tense, that is possible as well. As to whether it is easier for a Chinese poet to be vague about time and tense than it is for a poet writing in English, I leave that to Language Log readers to wrangle over.

First, however, here is one of my favorite Chinese poems (by Ma Zhiyuan [1250?-1323?]):

“Tiān jìng shā · qiūsī” Mǎ Zhìyuǎn

《天淨沙·秋思》馬致遠

Kū téng lǎo shù hūn yā

枯藤老樹昏鴉

Xiǎo qiáo liúshuǐ rénjiā

小橋流水人家

Gǔdào xīfēng shòu mǎ

古道西風瘦馬

Xīyáng xī xià

夕陽西下

Duàncháng rén zài tiānyá

斷腸人在天涯.

And this is my English translation:

Tune: “Heaven-Cleansed Sands”

Autumn Thoughts

Withered wisteria, old tree, darkling crows –

Little bridge over flowing water by someone’s house –

Emaciated horse on an ancient road in the western wind –

Evening sun setting in the west –

Broken-hearted man on the horizon.

Does the English translation fail to convey the timelessness of the Chinese original? When I read this poem — whether in Chinese or in English — I often think of the images as existing in an eternal present.

This article comes from: http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=3108